by Auke Jelsma

Christmas 2025

Schedule

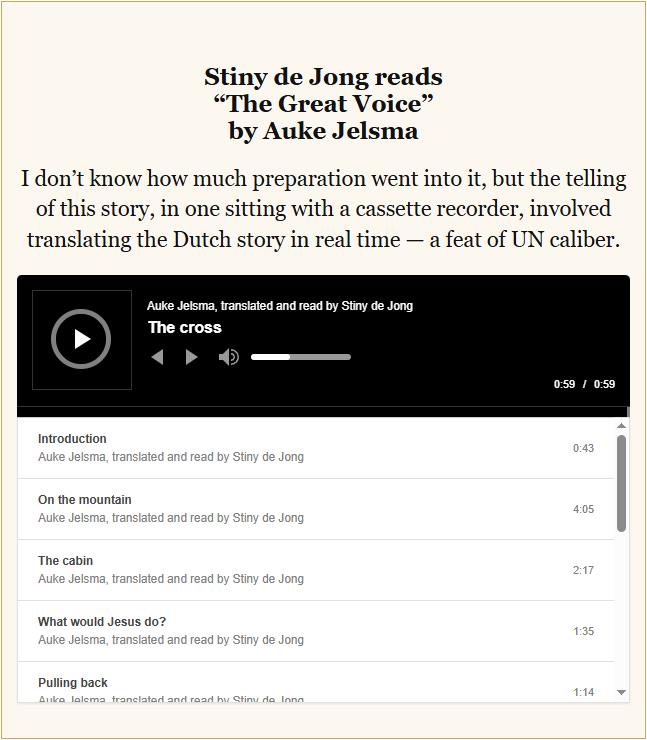

December 5: The Great Voice, by Auke Jelsma, read by Stiny de Jong

December 12: Aleb and the Wise Man, written and read by Herman de Jong

December 19: Our Story, by Henry de Jong

December 26: Johan, by Herman de Jong (English & Gronings)

Enjoy also these Christmas songs

played by Herman de Jong

on the Covenant CRC organ,

Auke Jelsma published this story, in 1954, at the age of 21 in a Dutch periodical. From there, that periodical was carried across the ocean to Canada by visitors to Herman and Stiny de Jong. The story was treasured for almost four decades before Herman and Stiny brought it back to life in, 1992, as an English audio recording. Now, seventy years after publication, “The Great Voice” is being re-presented with a newly transcribed text.

Provenance

The audio for this story has been online for some time already, and from there can be played while reading this text.

A cassette tape is all that remains of this in the family. From it, Audacity was used to generate an MP3 and from this, Tactiq was used to generate a transcription.

The cassette was produced by Herman and Stiny, ~ 1992, for their children and grandchildren then living in Africa.

Introduction

by Stiny de Jong

( ~ 1992)

Now I’m ready to read you another story. And this story is called “The Great Voice”. I have it here with me in a little book, that Dad bound together many years ago in the fifties, of Dutch poems and Dutch stories. It’s written by a man named Auke Jelsma called “The Great Voice.” And I have it here in front of me in Dutch. So, I’m translating as I go along. I’ve read it before, and Wayne and Marcia may remember it, and Henry and Wendy, and maybe a few older children. But the young children probably, it will be new for them. And I’ve always loved this story, and I hope you will like it — to hear it again too. So here we go.

The Great Voice

On the Mountain

I’ll introduce myself. My name is Sepp, and I was born and raised in North Switzerland, near a small village called Frick, a little place with white houses and two small church spires, bedded in between the mountains, slopes full of cherry trees. God pulled a line through the village with a river, a foaming crooked line. He didn’t do that because he didn’t like the villagers, but he did it out of love so that the villagers could drink from the cool fresh water.

My parents farm lay a few mountains further and it was like an island in a sea of trees round about. There were about ten gnarled, crooked cherry trees all around the farm, and it was incredibly lonely and deserted there. You never heard other voices than those of your family or of the birds. And then there was the snapping of branches and the moaning of a little brook that, just behind the low-lying farm, was being beaten on the rocks. High above the tree line were the bare treetops, green with meadows. And it was there that, in the summer, our small red-brown cows wandered around with bells around their necks — bells that glinged and tingled brightly with their movement.

After my eighth year, it was my task to watch over them, day and night, because I couldn’t yet do the heavier work. Only in the morning and in the evening, my mother and Rosemary came to milk them. But that didn’t last very long. As soon as the sun, which was like the eye of God, disappeared behind the mountains, they disappeared to the cozy living room full of kerosene light. They gave me one more kiss. “Grüße,” they said. From a small mountain meadow deep below me they would wave at me one more time and I would wave wildly with both my arms to the disappearing figures, and also to the disappearing sun, longing for their return, while the cows were chewing their cud. And then I was all alone.

But I could see very far. When it was very bright, I could see at the end of the world, the top of the Jungfrau, which was plastered with thin layers of snow. And every morning, I saw the sun go down. And often, I had clouds under my feet.

Because I grew up so alone, without any contact with any other boys, instead of going to school my mother taught me in the winter — math and reading. And in the summer, I did math and reading by the cows. And that’s why I long believed in the fantasies that a child has, and that you hear. I believed in gnomes and fairies until I was twelve or thirteen

I also believed that everything around me was alive. A tree was somebody — a mysterious somebody that was standing still during the day, but at night who knows what kind of travels and journeys it made. A brook was a living being, and I always felt sorry for the little river because it was being beaten so on the rocks. Even now I can never help but think that a little brook is in pain.

If I had always been with boys, they probably would have taught me not to dream like that. But now I kept on dreaming and believing in my fantasies, while the cows were slowly pulling the grass from the rocky bottom and their bells were tinkling. From all of this, all my dreams about the cabin can be explained.

The Cabin

I was eight years. The first summer of my loneliness lay behind, me when I discovered it. It was a few days after Christmas. I was still very much impressed by the story of Jesus birth that my mother had told me by candlelight. And I was wandering around in the snow, among the bare, gray trees. Suddenly, high above me, above the tree line, I saw a black dot, in the white, on one of the mountain slopes. I was curious, and I started climbing towards it. And as I was going, the black dot slowly became an old mountain hut. And I didn’t think that I had ever seen it before. It was deathly quiet there, and endlessly white. Mysterious.

And as I stood in front of the cabin, the thought suddenly occurred to me that this is where Jesus was born a couple of days ago. I knew it. It had to be. This is where Jesus was born. Here was the little Godchild, of whom Mother had said that it had come to earth also for me. I wanted to open the door to adore the child, just like the shepherds and the three wise men from the East.

But, for one or another reason, I didn’t dare. I sort of walked back and forth in front of the door, a black door with a couple of boards that had been nailed on it crookedly, and I counted the buttons on my coat. Shall I go in, shall I not go in. Yes, no, yes, no. The difficulty was, I didn’t know what the holy child would do if I disturbed it. Maybe it would smile with his big dark eyes.

But maybe Jesus would be angry, too — you never know with holy children. Shyly, not being able to decide, I finally walked away. But I kept looking back to the lonely hut. And in that pure, undisturbed snow, there was that double trail of children’s feet right up to the cabin and back.

What would Jesus do?

In the evening, I asked my mother what Jesus would do if I met him. Of course, I didn’t tell her the reason for this question because it was such a wonderful, wonderful secret that I didn’t want to tell anyone. I never told anyone all my fantasies and dreams. Tensely, I waited for her answer. This was very important for me.

“If you would meet Jesus, then he would put out his hand to you and he would say to you, ‘Sepp, I came for you too,’” said my mother. And she thought that the question came because her story had made such a deep impression on me. Later on, when I was in bed, I saw it happen. I pushed open the door of the hut and immediately Jesus smiled at me as if he had been expecting me and he stretched out his hand toward me and said, “Sepp, I came for you too.” I heard him say it so clearly that I looked around. But I didn’t see anything in the night, on my bed.

The next day I went to the cabin again. First, I made a great big circle around the hut. But gradually the circles became smaller and smaller while I, in my imagination, thought how it would go. The door would creak, eyes would smile, an outstretched arm and the words — the words that made you so warm inside — “Sepp I came for you too.”

Pulling Back

But when I finally was close enough to the hut to touch it, I suddenly didn’t dare to go in anymore. There was something in me that knew, vague of course and far away, because what does an eight-year-old boy know about the background of his thoughts and his deeds when even adults don’t know? I was afraid that the dream would break. But for one or another reason, I didn’t want to make a reality of the dream.

Much later I realized that I only knew that I didn’t want to go inside, and yet I longed to go in. Without doing anything, I turned back along yesterday’s trail. The days after that were fully filled with lessons and running errands to Frick and other little jobs that are always there on a farm, so that I never found time any more to go to the hut, and I could only long and dream.

After supper, sometimes, there was time but then I didn’t dare because I was afraid of walking trees. And when the snow had melted, I never had a chance any more to go because there was so much work to do, by which I couldn’t be missed. And slowly the memory faded.

The Next Winter

Not until the next winter did I visit the cabin again. I was very disappointed at first. It was only a shabby hut, as there are many of them on the mountain slopes. A black little barn without windows, that’s all it was. It was made up from very heavy beams. In one of them a heart had been carved, and it was surrounded by two names. There was an arrow through it, just like you see many names and hearts carved in huts and beams.

There was nothing special about it that it could be the cause of so many expectations. And yet, while I leaned against the back wall, I thought I heard a small child cry from inside, and suddenly that early certainty came over me again; here lies Jesus and he’s waiting for me, waiting until I come inside. It wasn’t even Christmas yet. But I didn’t think about that.

Suddenly I knew it. I just knew it for sure. I only needed to push open that old door and Jesus would smile, glad because I had finally come. His arm would stretch out toward me, “Sepp, I came for you too.” But when I stood by the door, ready to adore him, there was that strange feeling that kept me back — an unwillingness to go inside, while everything inside me longed for it.

I can’t really explain it, but it comes down to this; that without doing anything, I walked back through the trees, trees that had arms that were trying to grab me. And over the next few days, I kept being pulled back to the old hut. And I would be leaning with my ear against the back wall listening to the possible sounds that the child would be making, longing to go to him yet not wanting it.

Suspicion

At a certain moment, my many trips were beginning to give rise to suspicion at home and my mother asking where on earth I was always going. Father put the paper down on the table and looked at me expectantly. Rosemary stopped knitting. But I didn’t tell them. Of course I didn’t tell them. I didn’t even want to make the dream a reality myself, let alone I would talk about it with anybody else.

A shared dream is no longer a dream, but it’s a half reality. That’s why I sort of waved my arms and said, “Oh, I just go for walks,” knowing that it sounded very unlikely, and they didn’t believe me. “I’m sure,” said Rosemary, “mister is just going for some walks.” I looked at her full of contempt, but I didn’t answer. My father shrugged his shoulders and picked up his paper again.

Deceit

The day after this conversation, I struggled through very heavy snow all by myself on my way to the cabin again. Halfway, I happened to look back and just saw my sister hiding behind some shrubs. I was furious about her spying on me and, without giving any inkling that I had realized she was following me, I made an enormous journey over mountains and through woods and through cherry orchards, in a really wide circle all around our house. Of course I stayed far away from the cabin. I took care of that because I didn’t want anybody else to know my secret. I wanted to keep Jesus all to myself.

Close to the farm, I turned around and I stuck out my tongue, long and hard to Rosemary, who was staggering toward the house, exhausted. I saw her blush, fire-red, and I smiled and walked inside. It often surprised me later that I could have been so cruel when I was yet so small. That evening, I just relished in the secret that I had, the secret that was only mine.

The door opens, I smile, an outstretched arm and the words, “Sepp, I came for you too.” But you know, it was strange. This time the words didn’t make me warm inside. Instead, I was shivering in my bed. The strange thing was that that cold feeling stayed also after that night. My longing to find Jesus had frozen.

Revisited

I still regularly went to the hut, not quite as often as before because I was afraid to be followed, but it no longer moved me or touched me. After that day, I suddenly didn’t want to go inside any more to hear those words, to see those eyes and that outstretched arm. The dream had stopped dreaming and because there was no reality in its place there was only an empty indifference.

From time to time, I tried to rekindle the old feeling, but it just didn’t work. I longed for my longing, but it didn’t come back. And, finally, also these attempts stayed behind, and also the trips, and that indifference over against Jesus lasted many years.

Looking for Jesus

It wasn’t until the summer of my thirteenth year that I went to look for Jesus again. It was like this. I was lying in the grass watching the cows, the cows that were wandering over the slopes with stiff legs, and I was just letting my eyes roam over the entire scene. And suddenly I saw, at the end of the world, the mysterious glistening of the eternal snow high on the mountains.

Everything in me became quiet at this majestic scene, except for one thought that just rose in my consciousness without any connection with the Jungfrau. “I wish I could have a look in the cabin.” As I was thinking this, I jumped up and I ran away without even thinking about the cows in the meadows.

After some time, I saw the cabin below me. The roof was overgrown with moss and with grass, and a swarm of starlings just rained down on it. As I was going, I was imagining what was going to happen now, because this time I knew I was going to do something — I just felt it in my bones. All the forgotten dreams came to the surface again, and I remembered the arms, the creaking door, the face that lit up with a smile, the outstretched arm and the words, “Sepp, I came for you too.”

Maybe it’s strange that a boy of twelve still thinks of such things. You may think it backwards, but it’s a fact that, under that roof, I was expecting Jesus. Maybe not as a baby, like before, but I expected him alive, alive and well, and my heart was pounding in my throat as I walked towards the door in the sunlight. The starlings flew up startled as I arrived, and so it happened, what all those years I had imagined.

The door opens

The door creaked and opened slowly, very slowly. Bursting with tension, I stepped inside, hesitating with bowed head and filled with a holy adoration, over the low lintel. Carefully I looked around, in the half dark. At first, I didn’t see anything because of the contrast. But gradually the holy of holies took shape. A beamed roof, cobwebs reaching down to the floor, black smoked walls, an uneven floor full of knobs and holes and dirt and nothing else — just totally nothing else. I think this was the biggest disappointment that I have ever experienced. All my expectations exploded and vanished.

I tried to swallow my sorrow and my sadness, but I couldn’t. And I kept looking round and round, hoping, hoping something was escaping me, hoping for a miracle. When I had gone inside, I had realized that there was a terrible smell here. And as I looked around, I saw, instead of the miracle, the cause of the stench — some excrement, black with flies.

I was so devastated by the contrast between the dream and the reality that I had to grab hold of the wall, not to fall. As I grabbed hold of the wall, I felt a knob that I could hold onto to keep my balance. And then I hastily let go of the wall and turned around to go out to the sunlight and the cowbells and the eternal snow. But at that same moment, the knob that I had been holding onto fell — came off the wall and clattered down to the floor.

The cross

Curiously I bent over and picked it up. That knob of dirt turned out to be a cross. The whole form had become knobby because of all the cobwebs and other dirt. I held that simple object in my hands. Someone must have forgotten, I thought, looking at the simple wood carving.

But, while I was standing there with that cross in my hands, there was suddenly a great voice that filled the entire cabin — all nooks and crannies. A great voice that filled my entire heart, “ Sepp, I came for you too.” I looked around but I saw no one, and yet I knew who was there, and with the cross in my hand I walked towards the sun.

Auke Jelsma

Auke Jelsma (1933 – 2014) was a pastor, church historian and author, who served some time at Kampen University.

His age was in between that of Herman and Stiny de Jong, and Jelsma would not likely have been known by them before their emigration in 1953. At the young age of 21, Auke published this story in Ontmoeting, Volume 8 (1954 – 1955)

This was Jelsma’s second published story, in a list that extends to 1997. Auke Jelsma is still served by his own website, aukejelsma.nl