My nickname was ‘Jeude’ (Jew). My brother Kees was called by that name because he had black hair, and when he finished elementary school, that nickname was loaded on me. One Saturday morning I was walking downtown, close to our church. Onno Bolhuis passed by on his bike and waved at me. “Ah, die Jeude!” Immediately I felt a hand in my neck. A W.A. man! (He belonged to the political party which sympathized with the Germans and their members often dressed in uniforms, aping the Germans.) This fine Dutchman took me to the W.A. office where I was interrogated. Are you a Jew? (Most Jews in the city of Winschoten had already been transported to German concentration camps, of the 150 only 5 came back alive). I said no, of course not, that’s just a nickname! “How can you prove that you are not a Jewish boy?” I thought for a moment and then I told them that Rev. Berghuis who lived close by could tell them I belonged to his church. A few minutes later Rev. Berghuis came walking into the office, and soon the problem was solved. But did he ever scold these collaborators! Was he ever angry! I had been quite calm up to that point, but when the minister told these guys what he thought of then, I suddenly began to tremble with fear.

As the war progressed and I became older, I began to understand better what actually went on. I began to hate those Germans like older people did. And of course, the war influenced our manners. Even I became kind of a rough, wild kid. We imitated the battles which went on in Russia and North Africa. We formed street gangs and after school we would take our positions in dug-out forts, spying on the enemy which kept creeping up to us through the fields. One of these enemies was my best friend Wouter Nanninga, but that didn’t matter. It was only play! Our street gang had a sharpshooter. With his small catapult he could shoot sparrows out of trees. When Wouter approached our fort and came a bit too close, a little stone from our sharp-shooter’s catapult, made a dent on his forehead.

The next day they came at us with a long pole with a butcher’s hook attached to it. We fled in panic! All the same, during these street fights quite a few wounds were inflicted … and we gloried in suffering.

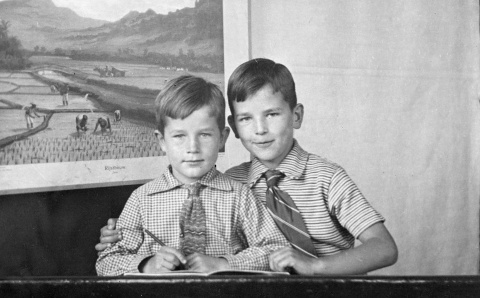

One of my best friends during the war was Henkie Driegen, who lived in Nieuwe Schans, a border town appr. 20 km. from Winschoten. He came to school by train every day. Sometimes he stayed at my place overnight, and a few times I spent a weekend with him. His father was a customs officer, but also worked underground to fight the Germans, even though his wife was a German woman. These visits to Nieuwe Schans lasted till 1944, when it became too dangerous to travel by train, as Allied Spitfires would strafe them.

With Henkie I witnessed such a strafing at the station square in Nieuwe Schans. We had been swimming – the swimming pool was in front of the train station – and were on our way home. Suddenly 5 very low-flying Spitfires thundered over us, made a beautiful circle in the air, and came back with guns spitting out bullets at the waiting train behind the station. We were too stunned to walk away. It was a beautiful sight to see these sleek airplanes dive down and pull themselves up again. As the square filled with steam from the damaged locomotive, we came to our senses and noticed hundreds of brass bullet cartridges around us. Quickly we filled our pockets, until a policeman chased us away.

Late 1944, I saw the same thing happen again, but this time the planes shot at a bus filled with German soldiers. With my father I had gone to one of our two little garden plots outside the city. We were digging up potatoes for the whole winter when suddenly I heard the planes coming and saw the bus on the road. My Dad kept on working since he was deaf and probably heard nothing. When the planes were almost overhead, he had that startled look on his face, and ran to the ditch, pulling me along. Up to our middle in ice-cold water we peeked over the potato plants and saw the soldiers spill out of the bus. Soon the bus burned up completely. We continued working as if nothing had happened … my Dad was good at that stoic behaviour.

In 1945 these 5 or 7 Spitfires would strafe trains weekly close to our home, often at night, because the Germans must have known that day-trains would surely be hit. Years later, when in the summer holidays I was weeding beets on a field adjacent to that railroad, I still found many cartridges. I left them in the field for they had become rusty.

At home we huddled around the stove in the winter. Only our living room was heated (with peat). Father had enough connections in the ‘peat’ world to make sure that usually we had a good supply of it, but he had to buy it clandestinely, and the square or oblong turfs had to be hidden in the crawlspace under the floor of our living room. To stack them up was my task, for there wasn’t enough room for grownups. Peat has fleas in them, and soon they attacked us in our beds. We chased them fervently, for they made your body itch fiercely. We killed them between the nails of our fingers.

One day, as we were working in our garden at the end of the Acacialaan, my father stared at his shovel. He had been digging a bit deeper in the soil for one reason or another. Suddenly he whooped: there’s peat under our garden, 75 centimeters under the surface. It was a kind of a loose peat, no sturdy peat-blocks as we had hidden under the floor. Nevertheless, it would burn! By the way, peat is coal in its beginning stage. Now my Dad was in his element. He loved to dig in the soil. So would I later on in life! We had to turn over 75 centimeters of good soil before we reached the peat, and it was my job to bring the soggy pieces home on the wheelbarrow, for if we left them in the field to dry, they would soon be stolen. Soon our neighbour gardeners did the same thing. Most of them gave up after a while because it was heavy work, but my Dad persevered. Towards the end of the garden the layer of peat became thinner and thinner, so we had to stop.

Leave a Reply