The family and its circumstances during WWII

Birth

How should I begin? Perhaps with my birth in Blyham (NL) on 3 October 1936, as told by my Mom many years later.

Could a time be darker, a place be humbler? Hitler tightening his grip on Germany’s people, raucously goading them towards catastrophic war. A small farm on a dirt road near a nondescript village in Holland’s Northeastern province, a mere ten kilometers from the German border.

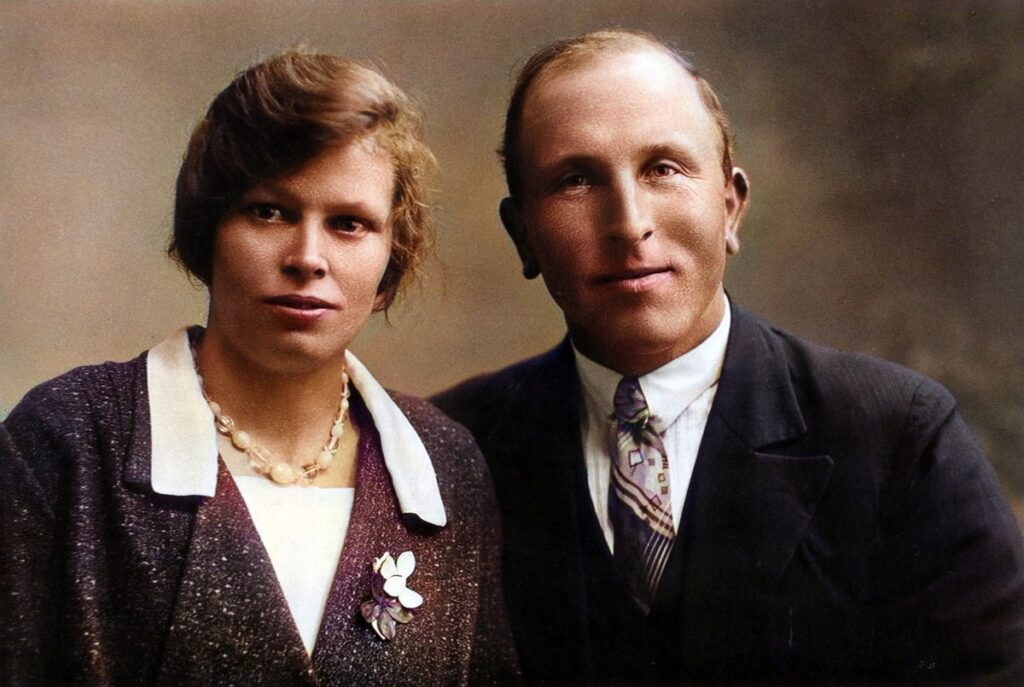

Young farmer Harm takes his daughter Stiny, not yet two, to neighbour Mrs. Kuper: “time to get the midwife, Dina is in labour.” He jumps on his bike and pedals hurriedly to the village (Blijham) two km away to call on the midwife whose help was arranged; she is not home, there’s another birth in town, but her husband knows where. Harm finds her, she is washing up and promises to be on her way in minutes. He does not wait but speeds back, bumping along the narrow foot and cycle path through grain and potato fields already harvested, oblivious to the mild October sunshine of late afternoon.

He soon reaches the big farmhouse, where he finds Dina calmly preparing towels and portable washbasin, heating water on the turf burning stove. “She is coming, will be here in a quarter hour” he pants. She holds him briefly, “thanks Harm, we’ll be fine, I am ready”. He kisses her, she senses his nervous warmth, strokes his face and his balding head, smiling. “This is a happy hour, I am strong and the midwife has done this a hundred times, don’t worry so”. He goes to feed the calves and pigs.

Into the future

Labour in the bedstead, soothing words and muffled cries from the upper room. It is an hour before midnight when she is delivered and Dina, 31, now mother of two, cradles the boy against her breast, joy pushing earlier pain to memory space. “Little boy be welcome, Harry is your name. No, not Harm, I do not want a ‘little Harm and big Harm’ or ‘young Harm and old Harm’, you are Harry”. The father, in tears, nods agreement, Dina knows best, always does in the practice of things. He strokes her and the boy in one movement of his huge farmer’s hand.

They have a girl and a boy now, he is 35 years old, a small tenant farmer, strong and modest, secure in his marriage, respected in his church community, with enough hectares to make a go of it, cows and pigs, growing grains, potatoes and beets, a farm hand to help, two horses for work, the small world is whole, the big world is rumbling across the border. Where will the life Harry has begun lead to, Harm wonders. The mystery of new life and the opacity of their future leave him in awe. The midwife sends him to the guest bed.

Sky fights

My first memory must be from about the late spring of 1940. I was three years old, the war was bursting over Europe, Holland had been overrun in a few days of Hitler’s Blitzkrieg, early bombing raids from England towards Bremen and Hamburg, to the east of us, changed our skies, especially when German fighter planes came to meet the attackers.

I was standing one late afternoon, hand in hand with Dad, Mom next to him, with our farmhand Danny. The adults were tense, listening to distant screaming engines and staring intently to see the planes in a cloudless sky. I sensed the fear and the stress, never before had felt that parents were anything but confident and strong. Foreboding.

Harry’s ladder

On a lighter note there is another early memory, perhaps also from the age of three. It was a warm sunny day and I was barefoot in the garden when I noted someone had put a harrow on its side against the barn so it now looked like a set of ladders side by side. I knew a ladder and how you could climb it, so this seemed inviting, especially as there was no one around to forbid it. It reached up to the red roof tiles and as I climbed to the top of the harrow I found I could wiggle onto the lower end of the roof by grabbing the longward edges of the thick tiles.

Here I was, on my tummy, peering upward and seeing the endless tile spines go up to a blue sky. I wiggled up further and soon got the knack of it. The tiles were dry, had a bit of algae growth that gave nice hold on my bare knees and feet. There seemed nowhere to go but up. I went, one tile at a time, never looked back, just saw the parallel track up to the blue sky. After a time and an effort I reached the barn roof spine, climbed to straddle it.

Finally I lifted my eyes and saw a panorama totally new and unexpected. Amazed I was and delighted. Here was the huge double expanse of the whole barn roof sloping to my right and left. Then the entire hamlet, I was looking down on smaller houses, on our yard and that of neighbours, the fields, the tracks and the cycle and foot path, the road to Winschoten, the windmill, the town, in fact the tower of Winschoten, the factory chimneys of Pekela. Everything I knew about even vaguely or not at all. Here I had the first helicopter view avant la lettre and I was so excited that when I saw Mrs. Kuper next door at her clothesline, I shouted her name.

She looked and looked but searching low did not see me. ‘The roof, the roof’ I shouted and then she saw me, little guy on a barn roof. Stunned, she dropped her wash and ran to call my Mom, who came to the garden, flabbergasted. ‘Harry what on earth are you doing up there!?’ ‘Mom I see Winschoten and everything, oh Mama it is very nice.’ She stood nailed tot the ground, then said in a controlled voice: ‘Sit still, I ‘ll be right back.’

As she went, I resumed my tour d’horizon with continued delight. Apparently Dad and Danny were in the stables because they were there all too soon. Danny used my ladder too and came shuffling up the roof while Mom spoke soothingly about good boy stay put. When Danny was within reach, he turned and sat next to me just below the spine. ‘Ok little son-of-a-gun, come sit between my legs.’ Together we carefully slithered on our bums down a tile track where Dad took me at the bottom of the harrow.

Everyone seemed relieved, there came a light but clear reprimand, then my usual whipped raw egg with sugar and cinnamon, which I always got at morning coffee time, — ever since my Oma Van der Laan told Mom at my first birthday that I was weak and not a blievertje, not someone to stay — and now I knew what those gulls see when they float above our house, I envied them so.

War guests

It seemed not long before our family life changed drastically. New inhabitants came to live with us. They were called onderduikers, literally underdivers, people who had to disappear from public view. The first two were Mr. Schonewille and his son Jan. It was 1942, they had both demonstrated against the occupier in a national railway strike and feared arrest. Soon there followed a young man from The Hague, Kor Nicolai, who did something in the underground movement and then the Reverend dominee Hommes, who had preached a fierce anti-Nazi sermon. So instead of six (including Danny the farmhand) we were now ten at midday dinner.

The onderduikers slept inside our large hayloft, which was built around a clever pole construction in the front barn loft, with a concrete conduit as a tunnel into the sleeping space and with cardboard tubes, lightly covered, for ventilation. Now and then Henk and I were allowed through the tunnel into this big hollow, lit by one of the men with a hand-driven dynamo pocket light. That was exciting. Sometimes other men came, alone or in twosomes, to stay a short period. Those days were tense, the kitchen was really too small, the hollow too confining, the tension hard to bear.

Keeping secrets

Our Mom had told us with great care and with some repetition, that we were under no circumstances to tell anyone about the onderduikers. She said that if we did and people heard about it, German soldiers would come and take them away as well as our Dad and that he might never come back. This message made a deep impression on my six-year-old self and presumably on eight-year-old Stiny and on Henk, not yet five.

I understood later that we had several advantages as an onderduiker refuge. It so happened that the other six houses had no children as young as we were, so no playmates on the yard or in the house. Our hamlet was isolated as there was no asphalt road and the horizon was free of shrubs so you could, from the living room windows, see vehicles come on the two dirt tracks and on the path at a distance. Our garden was on the side of the house away from the path and the neighbours’ view and it had a thick hedge around the vegetable part, so the onderduikers could be outside and work there unseen.

None of our neighbours belonged to the pro-Nazi NSB, the national-socialist movement. Finally our police chief, veldwachter Broester, was on our side and would give warnings of possible raids or inspections. It turns out, miraculously, we never had a raid in those three years, where house and barn were searched, although we did have soldiers at the door asking questions. Once Dad was arrested when on the way on his bike to Winschoten and was away a fearful night. Apparently his questioning did not give rise to suspicions and he appeared unscathed the next day. Tears of joy.

Coping

Our Mom coped very well with all these circumstances. She had a talent for putting the involuntary guests to work, not only among the vegetables behind the hedge, but also with potato peeling, sweeping and dusting, washing clothes (no machines, so heavy work), etc. Mr Schonewille and son Jan did the heavier things, Cor, who was delicate, the lighter chores and dominee, he was reading, studying and writing sermons.

For Dad the full house seemed more problematic, he was often nervous and tense. I remember that once he had an argument with Mom at mid-day dinner and he jumped up, slapped her face and stormed out of the kitchen. Mom kept her cool, explained why Dad was so nervous and then went after him to soothe him. It is the only time ever I saw Dad commit any violence towards her. Then if you think about what were really life-threatening tensions . . .

Child’s play

For us children the unusual circumstances had their advantages. By 1942 many things people normally bought in shops were no longer available. Toys were scarce too and so the Schonewilles started to make them, sawing and cutting cars, trains, puppets, and horses out of wood. They also baked marbles from clay and painted them. These were not the best, easily broke up, but we could roll them all the way down our long hallway.

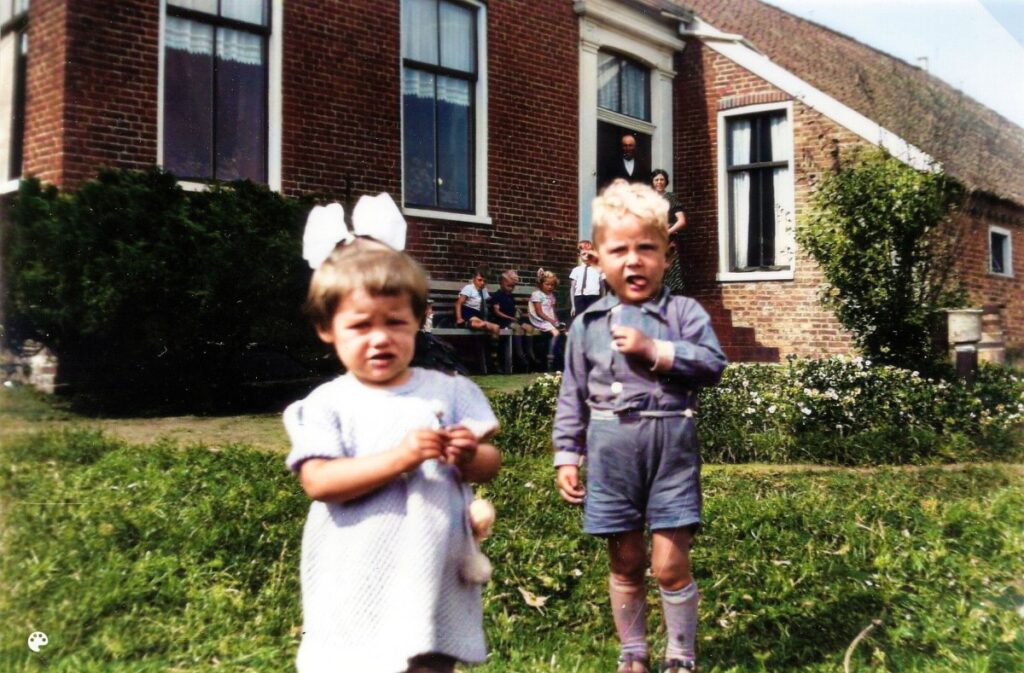

Henk was born only 15 months and 10 days after me, so I have no recollection of his birth. Our proximity of age meant he and I grew up together and on our isolated farm we were a twosome, always into things together. That stayed that way till we moved in 1945 and our range enlarged, physically and socially. I have told my children, when they were small, an endless series of Harry and Henkie stories, real adventures with some literary license thrown in, that stretch from 1943 to 1953.

Brother Co appeared another four years later and that five-year gap meant that Co and I really only started to be much aware one of the other, years later. Stiny is 21 months older than I and that big difference, plus the fact that a little girl had another life on the farm than little boys those days, meant our companionship was limited, we were children of the same parents but not playmates the way Henk and I were. I expect her stories and perceptions of our early youth to be very different.

Out in the Bouwte

We boys played outside as much as we could. The farmyard, the orchard, the hamlet area and the fields were all there for us to move in and move we did. As soon as the temperatures rose in springtime, we would take off our clogs and socks to walk barefoot. Our foot soles became very hard, not nearly as vulnerable as it looks. Also, we never really walked, we nearly always ran.

One of our favourite pastimes in the last two war years was collecting strips of silver and black radar decoys. These were spread all over our countryside, presumably by the RAF to confuse detection by German radar. The strips were of varying lengths and widths, roughly between one meter by 5 cm to 20 by 2 cm. We would collect them, sort them by size and roll them up. Dad would then know a use for them, probably selling the stuff to some flea marketer. For us the fun was in the action, not in the money.

Little bits of fire

Another even better field activity was starting fires in the potato fields after the harvest. The potatoes would be dug with forks and hands, collected in large baskets and moved to big mounds in wheelbarrows. The harvest began only when the plant foliage had died, was dried up. With the potatoes gone, the foliage would be gathered in large heaps and await a dry windy week. Then the fun began, the heaps would be set on fire and after a half hour or so a field would have tens of fires. We would find stray potatoes, skewer them on a stick, cook/fry them in the fire, strip off the blackened skin and eat them.

Of course there normally were adults present when this work was done. One autumn we could not wait and took our own initiative. I had a convex lens from an old lantern with which I could make fire when the sun shone. So one late afternoon Henk and I went to a field out of sight from the living room windows, plucked hands full of hay from field borders and started setting fire to a row of potato foliage heaps.

Problem was the heaps were dry on the outside, but not yet inside. So after a bit they began to smoke with an awful blackness from each heap, blackness that rose in columns and merged to look like a great fire. Soon all manner of curious people came running or cycling from Blyham to our hamlet, hoping to share in the excitement of a big barn blaze. Dad was not amused, Mom wanted to know where I got the matches. I did not reveal my ‘burning glass’ secret. Next day at school I was somewhat of a hero …

Family Guests

It must have been in the autumn of 1944 that one of Mom’s brothers, Oom Albert Beekhuis, and his pregnant wife Tante Ali with three year old daughter Frieda came to live with us. They apparently could no longer feed themselves in Oosterbeek near Arnhem after the Battle of Arnhem, well known from the movie A Bridge too Far. Well, food was no problem at our place and we had the space except for the kitchen, which by then was very crowded at mealtime.

Those guests put the upper room with its bedsteads into good use. Oom Albert helped with farm work. After New Year’s, Tante Ali and Frieda moved to Ali’s sister in Oude Pekela, a nearby town, for the birth of the second child; the girl Stina arrived in February 1945 and all came back to us. They stayed till after our liberation in April 1945.

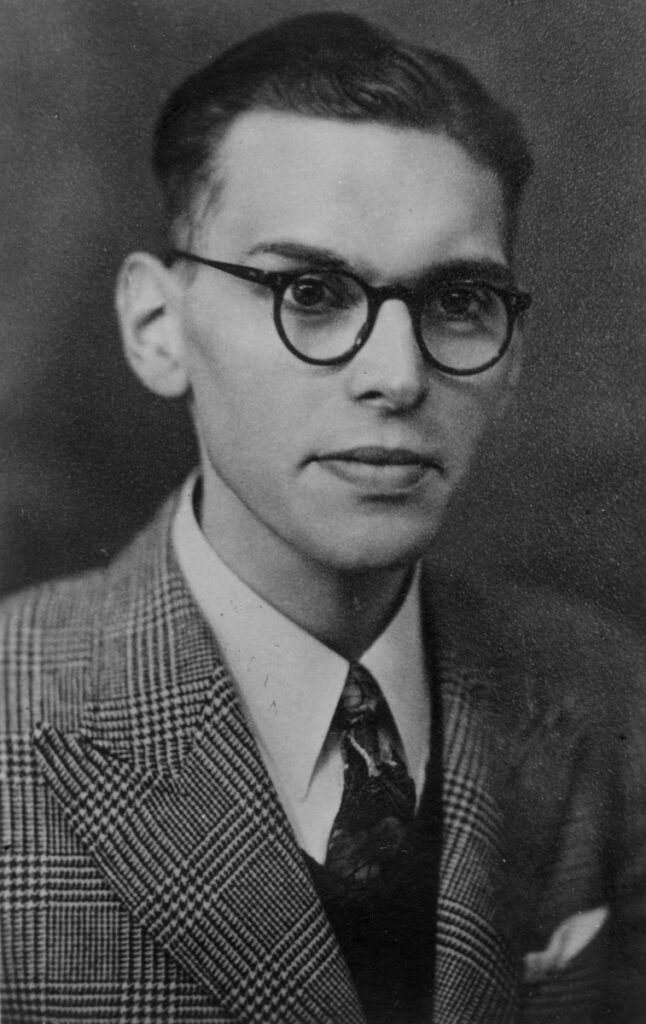

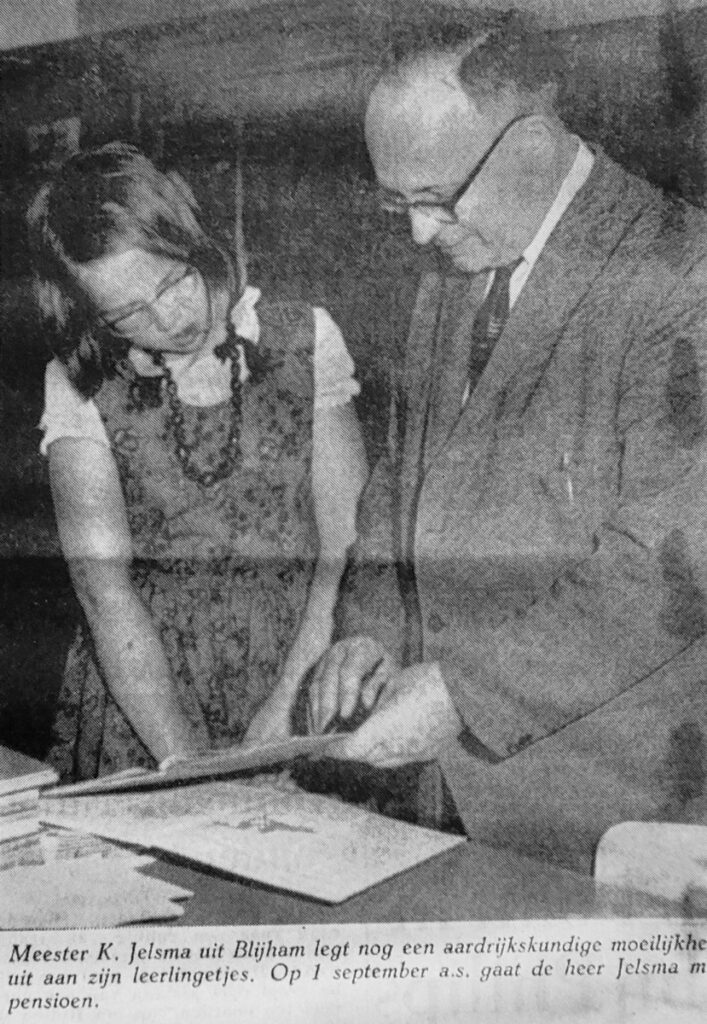

School days

I started school early in 1943, a two-classroom school-with-the-bible. The principal, Meester Jelsma had grades 4, 5 and 6, while classes 1, 2 and 3 were under the firm but friendly rule of Jufrouw Ms. Homan. Of course at first I walked with Stiny, about four kilometers, two to the town, two through the town direction Wedde to school.

I had to wear clogs — barefoot children were not permitted. Whenever it was more or less dry, I would take off my clogs, stuff my socks into pockets and run as Henk and I were used to. Stiny did not run with me. I soon found out that with a clog on each hand, one was well positioned to ward off enemies, be they dogs, tramps or other aggressive boys. In the course of my school life, I did use my clogs offensively as well I’m afraid.

School was interesting from the start. Ms. Homan and I hit it off well and I soaked up all she taught us. There were three grades in the classroom and many subjects were taught to one group while the other two were set to work. Of course, you could listen to the teacher speaking to a group not your own and so I learned a lot not yet meant for me, easy because I was fast at my own assignments.

I was fascinated by geography and biblical history as well as the games we played in the schoolyard, especially hopscotch and certain forms of marble competitions. At school I soon made some friends, with whom I sometimes went home after school. But I could not invite them to our place. Because we lived way out of town on a mud-track, this one-sidedness did apparently not strike anyone as odd.

A big change at school was the one of language. At home we spoke the local version of the provincial dialect, Grunnings, a derivative of proper Dutch ànd German. We heard Dutch daily in Dad’s prayers and scripture reading at mealtimes, from dominee Hommes and other visitors, and in church, but at home we spoke Grunnings — it formed our tongue and the fine motorics of the mouth, leaving an accent in Dutch that lightly stayed even seven decades later. At school and in the classroom we heard only Dutch and we had to speak it there. To this day I cherish my native tongue — it has a subtlety and humour that is emotionally unique. But Dutch and English are for me equally effective second/third languages.

Through the winters

Our winters were long — good thing we had lots of room and animals and onderduikers. With them we played hide and seek in the big barn and helped feed the calves and pigs. In the early evening dominee Hommes would occasionally be persuaded to tell a story. We children sat on pillows on the floor under the stove pipe, he in an easy chair next to the stove. The light would be a tiny oil lamp, really just a wick floating on rapeseed oil in a preserving glass. When we were very still, dominee would begin his once upon a time and fantasize wonderful stories in what I now call C.S. Lewis style. The other adults were at the big table and would listen too.

When the story was over and we sighed about the sadness or joy of the ending, two or three onderduikers, Dad and oom Albert would take turns mounting a bicycle, set in some wooden contraption so it was stable and the rear wheel off the floor. That wheel had two or three conventional bike dynamos on it and cycling at a good clip lit three small electric lamps by which people could read or darn socks. A fit man can keep going at a 150 W load for a quarter of an hour, so with four athletic types we had light!

We had no electricity from power lines in the second half of the war and frequently I went to one of the three blacksmiths in Blyham with some meat, sausages or ham to get carbide, a white smelly substance which gave off a gas when carefully dosed water drops fell on it. In a special lamp this was lit to give a very bright white light, for use when good light was essential. But the stuff was scarce, expensive and illegal, so we used it sparingly.

Butchering

Talk of meat and sausages, we always had a couple of sizeable pigs being fed autumn and winter for slaughter in the spring. We children knew that and could live with the thought. This was very different from our attitude towards the fate of the rabbits — big Flemish giants we kept, gave names to and cared for. They were destined for meals at Easter time and that grieved us no end.

But we loved the sausages and hams which we knew we could not have without the pigs’ sacrifice. When the butcher came for the kill, we were very excited. The day before, there were many preparations — pails and tubs were scrubbed as well as a big ladder with ropes put up and a big door was tied onto triangular frames.

On the fatal day the fattest pig was led to the bench, three men would grab her and throw her on her back onto it. Sometimes she would slide off and make a run for it. In the end she was always tied down and we knew what was next. Hiding behind straw bales or a wagon we would stare in fearful fascination as our pig screamed blue murder and the butcher plunged his huge knife into its throat, Dad ready to catch the blood in a pail. In a minute or two the screams would subside and the animal transformed into an object to be worked on.

An hour or two later, there it was, hanging cleanly on the ladder, snout down, the symmetric insides spread wide open, dark brown kidneys, two huge slabs of fat folded out of the rib cage. By then Mom had made blood sausage/black pudding and other products ahead of the butcher who would come back in about three days to turn a four hundred kilo object into hundreds of packages of many kinds, using pungent spices for some — packages for feeding our big family, for gifts to the needy but also for buying shoes and clothing! The merchants in Winschoten had virtually no stock, but they had to eat. When our parents went to town with butcher packages they usually came back with items that were ‘out of stock’.

Visitors

In 1944 during Pentecost weekend we had a visitor from The Hague, one Mr. Rietdijk. He was the father of Miss Elly Rietdijk, a girl in her late teens, who was staying with us for a few months to recover from undernourishment. The farm environment, with milk cows a few meters from the kitchen, hams and sausages suspended from the ceiling, a cellar full of vegetable preserves, butter, fresh eggs every day, an attic with well conserved apples — it must have seemed paradise to her.

It was a sunny Whit Monday and after the noon meal we played a kind of marble game with walnuts, apparently a tradition also known to our visitor. After that we played hide and seek with a tree to run to for refuge when seen. It was a lively time, the adults joined in and laughed and ran like children. Then, suddenly, I saw the running Mr. Rietdijk stop dead and flop down on the grass, where he stayed, motionless. Silence, then commotion, Elly crying on her knees, Dad going for his bike to get a doctor, Mom with cloth and water.

When doc Fiet arrived, Mr. Rietdijk had come to, bloodied forehead, bad headache, sore neck. He was a tall man and did not know our grounds. So he had run into Mom’s clothesline, a smooth tight steel wire hardly visible to a running person. He stayed in bed with concussion for several days and for a long time I could not evade that image of a vital running man arrested, slumping to the ground as though dying.

Hunger Winter

The winter 1944-45 was called hunger winter in urban Holland. Long processions of people, young and old, with bikes, handcarts, prams or just shopping bags, left the cities to swarm over the countryside in search of honest farmers. We lived very much off the beaten track and remote from major cities, but some found us nevertheless. Mom never turned anyone away empty-handed. She spoke with people, asked where they lived, what their family circumstances were, how they expected to get home with loads of food. Then she would decide what and how much to provide. Peas, brown beans, wheat and rye grain, some milk, eggs, a pound of rapeseed, a red cabbage, a few apples. As this eight year old stood there and saw the tired, skinny visitor light up, looking in awe at the abundance of this simple farm, I realized how well off we were.

The embarrassment came when either the visitor or Mom said ‘enough’ and payment was due. People would offer a ring, a gold watch, a broche with rubies, a string of pearls but Mom firmly turned all of these down. ‘No, I don’t know what that is worth, and you want to keep these as long as you can. Let’s just say three guilders.’ Mumbling thank you thank you, our customer would turn away as we wished them a safe journey home and God bless and keep you. Later we heard that many a walk ended at a checkpoint where German soldiers or NSB-ers confiscated the provisions gathered on a long journey, to cruelly send the exhausted man or woman home, empty handed to their hungry family.

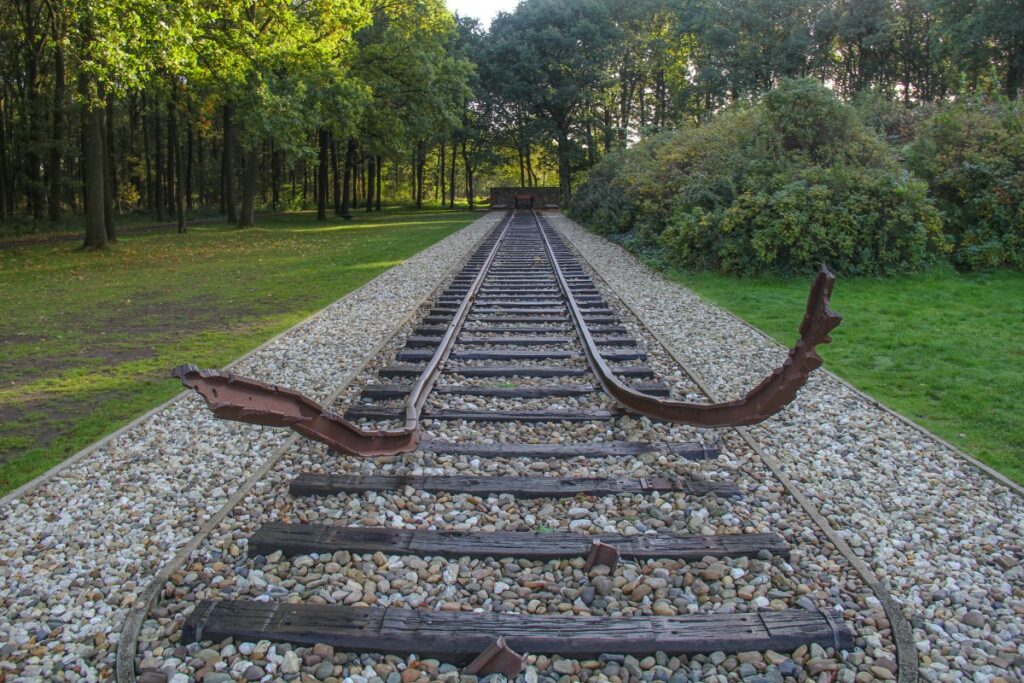

Jesus and Jews

As children we were aware, but vaguely, of the ravages of this world war. One Sunday morning on the way to church, Stiny on the back seat of Dad’s bike, I on Mom’s, — we had a girl looking after Henk and Co — we came to the Winschoten railway crossing and had to wait for a passing locomotive. I then saw a group of huddled people, children among them, in a long row across the rails on a freight platform, herded by several armed and shouting soldiers.

I was very disturbed, asked Mom “what are they doing, who are these people, why do the children cry?’ Mom said ‘hush, I’ll tell you at home’ and we biked on to the Reformed Church on Venne Street. It was full, the organ played a Bach Cantata and the whole service I thought about those children scared and cold — where were they taking them?

Once home Mom told me that these people were Jews and that the Nazis did not want Jews to live among us. ‘Would they have taken Jesus away too Mom?’ ‘Yes they would.’ And didn’t we all sing about Jesus this morning Mom, a whole church full? And could all those people together not stop those soldiers and take the Jews home Mom? Only in the dark, when they are not looking, otherwise the soldiers shoot you dead, the Jews and their helpers.

A few times, underground couriers came with several Jews to our farm to hide, to change clothes, to change courier, then to go again with food and drink. ‘No longer than twenty-four hours, we have our onderduikers, we are full, they will shoot Dad behind the barn if we get caught with Jews.’ We understood but after seeing that fearful group waiting on the railway siding for a cattle wagon, I always felt torn when there were whispering strangers in the hallway and when they left again in the dark. I know Mom let them go with a heavy heart.

The Boskers

The owners of our farm, to which Dad paid his quarterly rents, lived about three kilometers from us in the direction of Bellingwolde, towards the German border. They were two brothers, the Boskers, one a widower, one a bachelor. The bachelor was a tinkerer who had a workshop with advanced tools, including a mini-lathe. Always when Dad went there I asked to come and then I wanted to be in that workshop, smelling of machine oil, soldering iron and welding torch, right next to the kitchen.

The man took a liking to me and one day gave me a set of rails, three wagons and a caboose, plus a real, working steam engine! I, not yet eight, was in seventh heaven. Mr. Bosker showed me how it worked, where the safety valve was, how to fill and seal the boiler, how to heat it with a short thick candle. Mom found it dangerous, which is probably right, but as a compromise we could run it in the presence of Dad or Jan Schonewille. We ran it in the hallway, first on the rails, but then straight on the linoleum, a much greater range. Boy, that was fun. After a while, the adult presence condition wore off. One day a piston rod broke and the engine was useless. I got Mom’s reluctant permission to walk to the Bosker house for repairs.

So first the track to the Winschoten-Blyham road, then along that road to the fork where the big windmill was, then further, direction Bellingwolde. I got there and Mr Bosker was amused by my request, said it would take time and I should leave it there, come get it in two weeks.

On my way back, I was almost immediately met by military vehicles, German ones, hurrying towards the border. Trucks, half tracks with guns on them, open cars in camouflage colours and motorcycles, two soldiers on each, one with a machine gun at the ready. I got scared, I had heard stories of soldiers shooting at little boys for fun, so during a lull in the convoy I crawled into a ditch by the road and ducked every time I heard a vehicle approach.

Afterwards I realized that my blond curly head bobbing above the grass in order to look was probably a more interesting target than a boy in full view … Anyway, I got home, panting from a long and fearful run. It was March 1945 and unwittingly I had witnessed the start of the Wehrmacht evacuation from the Province of Groningen. Two weeks later we were liberated by a mixed Canadian-Polish brigade. I recovered my locomotive in May, laughing with Canadian soldiers who gave me my first ever chocolate bar.

Liberation

Our liberation, 11 April 1945, was a sensational day. The men in our house had designed and built an underground shelter about ten meters from the barn near the vegetable garden, a three second dash from the rear door of the hallway. The design was simple: a rectangular hole, 3 by 6 meters and 2 meters deep. Over it a roof of poles and chicken wire, covered with a thick layers of sod and earth. A molded staircase opening at the end nearest the house door and inside a long earthen bench on each side. Planks shored up the walls. It could easily hold a dozen people. Question was, when and why would we use it? For the time being it was one more place for playing!

Oom Albert was by then quite active in the underground movement; on April 12 he would appear with a carbine rifle and an official armband to prove it! He had some forewarning about when the liberation forces would move into Blyham and on the morning of 11 April, at his instigation, we were on our knees at the living room window sills, peering towards the Blyham-Bellingwolde fork in the road, less than two kilometers away.

Lo and behold, we suddenly saw tanks covered with large orange tarpaulins appearing from the Wedde direction. From the smoke puffs we thought they were shooting and then the wings of the windmill at that fork started turning and the whole mill burst into a wild blaze with long spark trails. A jeep appeared on one of the tracks towards us, stopping at the only farm labourer’s house along the track. We saw soldiers jump out and shout, then one threw a hand grenade into the house, ducking as we saw the explosion. Quickly they turned the jeep around and careened back to the road and in the Winschoten direction.

It seems incredible now, but oom Albert said ‘lets go and see what happened at that house’ and he ran there, with me on his heels. Approaching the place he waved me to stop and wait, went in, came out ashen gray, said there were dead people there, took my hand as we were running back. It is then I heard my first bullet whistling past us. Oh, said oom Albert, a whistling bullet does not hurt you..!

We got back and everyone was in the shelter, they had heard bullets too. Trouble with that shelter was you could, when you were in it, not see anything and we were terribly curious — back to the living room windows. It was then again we realized the advantage of living back there rather than near the asphalt road. Those liberating tank-cowboys were trigger happy. We saw no evidence of any resistance, but they shot in all directions and in addition to the grain-mill, burned down two farms, one of them friends of ours, the Werkman family. Dad and I went there in the afternoon and I was appalled by the looks of burned, bloated cows and poor Mr. Werkman in tears among the smoking ruins of his barn annex house.

Life after liberation

The liberation greatly changed our life. The tension fell away, the two or three onderduikers who were still with us of course went home immediately, the Beekhuis family moved into an upstairs apartment in a big farmhouse on the Blyham-Winschoten road. Suddenly the house seemed quiet — to us boys it felt empty.

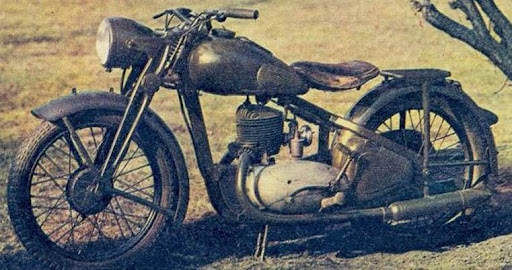

The immediate aftermath of sweeping away the remnants of German forces had interesting consequences for Henk and me. For several days German soldiers in tiny groups kept moving along the road towards Bellingwolde and the border. They were fleeing but had little choice for their route — all dirt roads and tracks were perpendicular to the asphalt road, so did not help an escape to Niedersachsen. The men, boys some of them, were in trucks, stolen cars, motorcycles, bicycles and on foot.

We saw two fellows abandon their JAWA motorcycle next to one of our fields, hide their uniforms under the grass, put on civilian clothes and proceed on foot. When they were out of sight we pushed the motorbike home, quite an effort for a seven and an eight year old boy. Oom Albert took that bike from us, managed to get it started and triumphantly drove to town on it, big boy of thirty-eight!

We went back to the place where the soldiers had hidden things and found ammunition, rifle and revolver bullets which we stuffed into our pockets and hid some under our pillows. Mom found them and gave us a tongue lashing. But we had in the meantime found lots more which we stashed elsewhere, not telling anyone.

Nearer my God . . .

The biggest shock of liberation for me was the death of a school mate, Lodewyk Holvast. It was my first death at close range. Lody was run over by a Canadian military truck in the centre of town. Probably, being used only to horse-drawn carts, he had overestimated the time he had to cross the street. The Holvast family lived very close to school and our whole class filed through their upper room, in one door, out the other and back to school. He was in the open coffin, Sunday-dressed and combed, waxen face with the hint of a smile.

Our class learned a hymn, Nearer my God to Thee …. which we sang at his burial insofar our voices did not break in tears. We felt as though we had a war hero of our own, torn from our midst. The stark irrevocability of Lody’s demise was a new, disturbing upheaval which for me meant for the first time ever, dwelling on my own mortality. But then in the rush of new life, we felt once more as children do; my future is forever.

Moving on

Dad announced one supper time: ‘we are moving to Wedderveer.’ Astonished, I shrieked with excitement: Wedderveer, that’s where my girlfriend lived and her brothers, my friends too. That was where the cafés and the playgrounds and the big public pools and the river were, an altogether more exciting place than the dull, backward Bouwte where we spent five war years plus the forgotten eons before that in the mud. ‘When Dad, and where will we live?’

Our parents told us that Dad had been awarded the lease of a rather bigger farm owned by an NSB-er who was convicted and sentenced to a seven year prison term for his treason. In fact, Dad had the choice of several NSB farms in the area and with Mom chose the place in Wedderveer, the place which for me became the home where I grew up. Our move was only a week or two later and it was on a school day!

This chapter is part of a larger work

— there are previous and next chapter links below

Leave a Reply