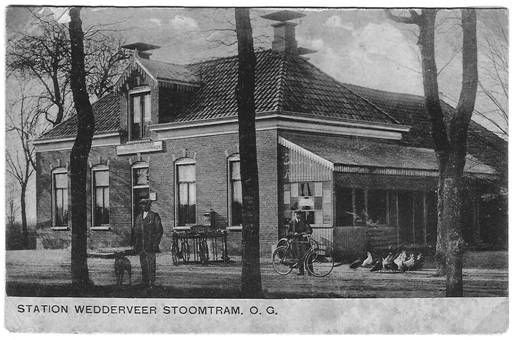

The farm in Wedderveer.

Note the fruit trees close to the barn, the orchard of the neighbour Begeman on the right, the tractor shed at the back, the vegetable garden this side the clothesline and the rows of potatoes between clothesline and shed.

On the left the small barn of our immediate neighbour Van der Meulen and the woods behind their house. After the harvest our whole barn was filled with grain except the very rear where the cows and horses had their winter abode. The big front door of the barn is matched by an equally big one at the rear so one could drive right through it. In the space between these two barn doors implements and the car were parked.

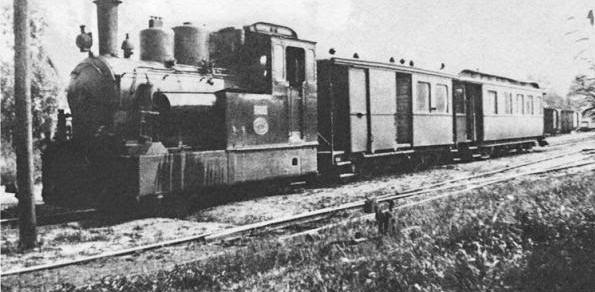

It must have been late August or early September 1945 when the big transition day arrived. We three school children left in the morning but not quite as usual. We had instructions to stay over at school for lunch and in the afternoon go with friends who lived in Wedderveer. They would show us where our new home was. So at four o’clock we and our friends were excited as we left the school grounds and turned left towards Wedde, not right towards Blyham as we had done forever. First thing that struck me were the huge oak trees that after only a few hundred meters from school, lined both sides of the road. That road wiggled gently with the tree tunnel, probably because the river a hundred meters or so behind the houses on the left meandered too. Clinging to the road exactly parallel was the narrow gauge track of the steam tram between Winschoten and Ter Apel, a tram we boys would come to appreciate!

Wedderveer had no official status, it was between the two sizable towns Blyham and Wedde which after the war were joined as one municipality. Wedderveer began at the point along the road where the river dike was so close to the road that no houses were built there on the left for about one kilometer. At the end of that kilometer was the splendid swimming pool and playground TRITON with a café-restaurant and further playground across the street. Triton had the reputation of a well run pool where the buildings were painted frequently and the water pumped up from the river was filtered in a large cascade of concrete sand and gravel bins – which formed the riverside border of the pool grounds – until it emerged from a pipe in the middle of a heap of rocks in the lower end -shallowest- pool. Triton became the place we regarded as our own, our parents always bought an all-family season ticket, so we could freely walk in and out past the ticket master. The great summers we remember of those seven years are all associated with Triton.

Past Triton there were again buildings on the left, first a small grocery store, then a double house, then a white house called Casa Blanca where my girlfriend lived with her Mom, two sisters and seven brothers. Then came the public school, the principal’s house, two more houses, another grocery store and then the second, bigger playground with behind that a big public swimming pool. This complex, called Klein Schveningen, allusion to The Hague’s famous sea resort, also had a major café-restaurant across the street called Hazelhof. Between these two recreation places, but then on the right were another four simple houses plus three farm houses with barns, all separated by generous gardens and orchards. On warm weekends Hazelhof restaurant and playground were crowded, hundreds of bikes, exuding a festive holiday atmosphere. We often slipped into that playground without paying and now and then got caught by a supervisor who would take us to the exit by an ear. The reason we did not subscribe to this place was that the water was not filtered and came straight from the river, a bit brownish with an earthy taste. Our parents thought this was a health risk and forbade us to swim there.

Past this playground the dike was again hugging the road -or vice versa- so no houses on the left. and after three modest workmen’s houses on the right there came a fine farm, looking new, bright red brick, neat house about half the width of the big barn behind it, to which it was attached. It was set about 25 meters away from the tram tracks with a well kept lawn with flowers, shrubs and several trees. The barn gable next to the house had a huge sliding door where the driveway ended, right in front of both kitchen door and main house door. The yard was spacious, continuing by the barn side and a large area behind it with a manure pile, a chicken house and -run and a tool- shed/tractor garage. There were large vegetable gardens annex orchards between our place and the previous house, separated by a thick high hedge. So this was the place our friends brought us to on that transition day and I was glad. Great village, fine house, splendid neighbourhood, and a tram in each direction each hour whose locomotive went chug-a-chug and whistle blowing next to the asphalt road, where the traffic consisted of an occasional truck, a few cars, horse drawn wagons and plenty of bikes. What a contrast with the house we left in the morning!

Life in Wedderveer soon stabilized, our school was only slightly closer than before, but we could no longer run barefoot because of the asphalt. On the other hand we soon got new shoes in which we could run, leaving our clogs for the farm yard. Our immediate neighbourhood was formed by us, a big double house to our right and next to that a white house that looked like Casa Blanca which was called Eben Haëzer. Across the street of this house stood a villa with modern rectangular architecture called Aa-stroom, after the river Aa right behind it. We soon learned that all three named houses were built by Opa Feunekes, Aa-stroom for himself and his wife, Casa Blanca, 500 meters towards Blyham from us, was built for son Lukas and Eben Haëzer for son Jan. Opa died a month after the war started and left wife Alida – oma Feunekes to us – and a daughter in Aa-stroom.

Lukas and his wife Gine had ten children and a thriving business best called threshing contractor. Behind the preceding double house and Casa Blanca there was a large common yard and a big workshop for machine maintenance. Jan and his wife Pia had four daughters and a son, but lost a daughter who was killed by the tram where the tracks crossed the road in front of their house. They had another daughter who was born early in 1946 and was given the same name: Jitske. Lukas and Jan were the age of our parents, so the ages of their children overlapped with ours and as we went to the same school-with-the-bible, we became good friends.

Jan was a farmer like Dad, had inherited the 50 hectares / 120 acres place of sandy loam, grew potatoes, oats, rye and barley and feed-beets much like Dad did on our newly leased farm.

Jan had one big advantage over Dad: he owned a prewar McCormack tractor of the type with big and wide rear wheels and a driver’s seat that really hangs behind the tractor over the implement that is drawn. Dad and his two farm hands Drewes and Heikens, had to do their work on an equal area with two or three farm horses, which was certainly slower and more tiring. Dad soon bought a Model A Ford modified to serve as a tractor but this proved unsatisfactory: large turning radius, narrow wheels to easily get stuck in the mud and a chain drive system where the chains frequently broke.

The Güldner

It was not till about four years later that we bought a new tractor for nine thousand guilders, a Güldner made in Asschaffenburg, Germany. It was a two cylinder Diesel with rather narrow wheels and tires and a high seat, a big contrast with the Cormack and a constant source of comparison and ribald remarks in both directions, tractor rivalry. I took a major interest in our Güldner, went to a course for engine mechanics (I was then twelve and by far the youngest participant in the group taught in a Winschoten hotel) and took to maintaining the thing. My fondness for the tractor was partly irrational, I would become furious when Dad did not switch gears in time or smoothly. Only later did I admit that while an animal or Dad could suffer, the tractor could not.

Dad in turn had an advantage over neighbour Jan: he took over the incarcerated farm owner’s shares in a cardboard factory called Reiderland and for several years got the shareholders’ price for all the bales of straw he delivered there. That price went up to 163 guilders per ton where the free market price, which neighbour Jan got, was only twenty or so. Dad told me the straw yielded as much revenue as the grain! Of course Reiderland in the end went broke, the shareholders/farmers had always put off investments to maintain the super price for their straw. But by then we were packing up to leave …

At the end of 1945, we were firmly settled in our farmhouse and neighbourhood, the big event was a birth. As I remembered from brother Co’s coming into the world, we were ushered to our neighbour’s house and there, in the big and chaotically cosy conservatory attached to their house on Eben Haëzer’s side, vrouw Jonker and daughter Siena explained to us, in some graphic detail, what a birth was all about and what started the baby in the first place. Siena was Henk’s age, younger than I, much younger than Stiny, but her Mom had already told her far more than birds and bees, a knowledge she was embarrassingly eager to share. At age nine I was flabbergasted and when Dad came to get us, shouting with a big smile about a new girl named Rika, I looked at him wonderingly: so Dad, you had something to do with this too, I thought, but would not have dared to say it. December 29 1945, a little sister named Rika, and our first human sex education. As farm kids we knew about animal sex but this was different … or maybe not quite as much as I had vaguely thought? From now we had baby Rika as our little sister and she would always have that status, for better or worse.

In the final war years our schooling had suffered from lack of fuel. When it was cold, we had lessons only half time. Our school year till 1946 went with the calendar year but was then changed into a semester system starting after the summer holiday. Because we had lost time and progress since 1943, our classes were put back one semester in the new system, so we could catch up. Of course this also made us that much older at graduation time, but then all schools had to be in step with secondary schools anyway, so it was inevitable. Mind you, I could have jumped ahead a semester with some guidance and encouragement, but that was not in the school’s interest, as it would have involved setting priorities, leading to controversies. Dad was on the school board …

We walked to school twice each way each day, sort of boring sometimes, any chance for adventures? Well, the old steam tram might just be chugging in the same direction at the same time and for boys used to running that was an invitation. If it had just crossed the road at Eben Haëzer, or stopped at the Triton tram-stop, it would be slow enough for us to jump on a sideboard for a free ride. Often the conductor would come, shoo us away, hitting on our fingers on the half door if we persisted. Better to jump on the rear bumper where he could shout at but not reach us. So routinely we rode two or three at a time for a good part of the way. We saw no risk except for an occasional chafed knee.

Cafe Heising

Steam tram

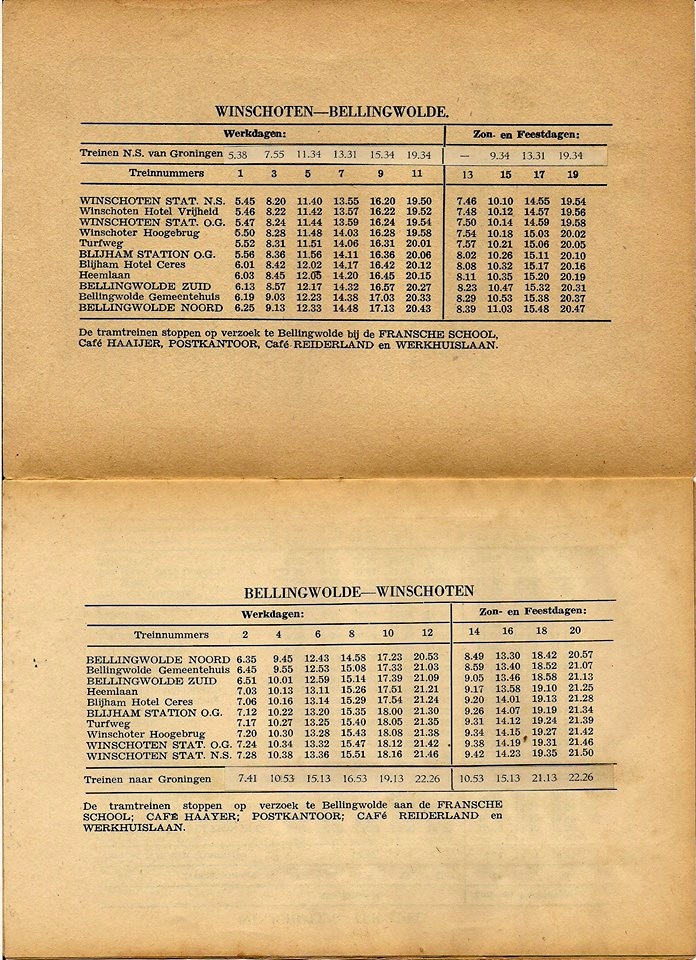

A Tram Line Schedule

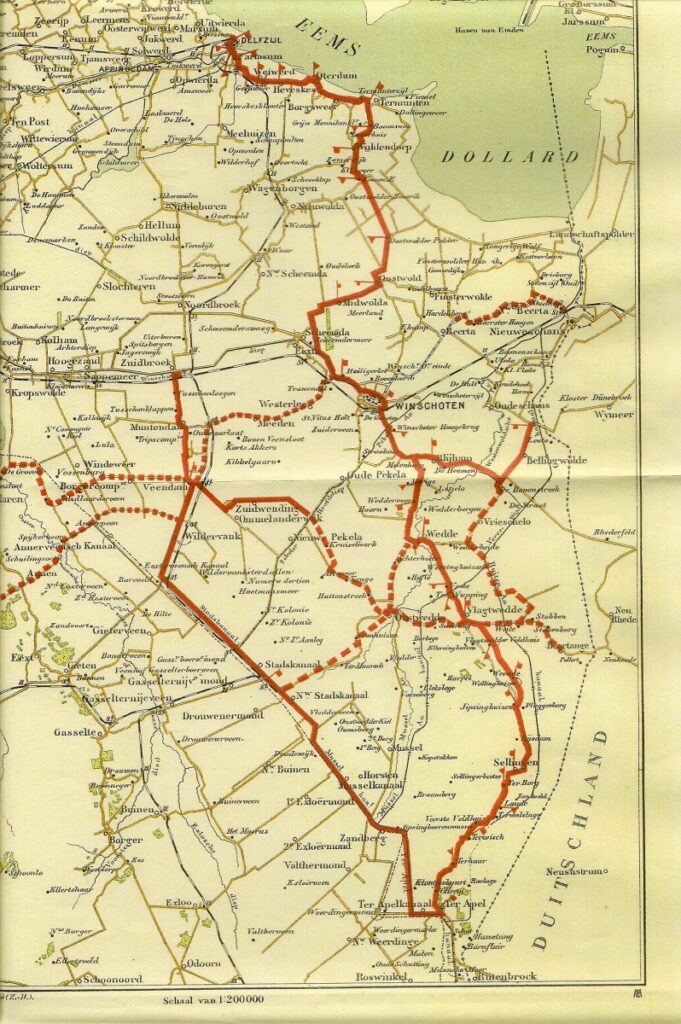

A Tram Line Map

A bigger hazard on the way to or from school was meeting a troop on the way to or from the public school next to Casa Blanca. They did not generally trouble us but unpredictably one of their bigger bully boys would challenge us on a point of doctrine as he understood it (usually a blasphemous caricature of course) and if the answer irritated them they might start a fight. We keenly missed our clogs and if we were outnumbered or outsized would run for it. After an incident we would for a day or two use an overgrown sleeper dike closer to the river as a detour and so avoid another clash.

I was nine when I made the transfer from juffrouw Homan to meester Jelsma’s classroom. Soon my relation with our principal soured. He did not like my quickness, my questions and most of all not my critical or correcting remarks. He became very strict with me and because I was extrovert and interactive, he always could find a fault and often did. I then got a scolding or five lashes on an open hand or had to stay on after school, write some dumb lines one hundred times or do something equally nonsensical. I was no diplomat -never became one really- and my protests at the unfairness or the wasted time only exacerbated the irritated relationship. I easily learned what had to be learned but found no inspiration in my teacher. My life was outside, with my friends -some would say my gang- out on the dikes, in rowboats on the river, on skates in winter, in the Triton pool in the summer and with my air gun shooting birds on the farm.

Now I do not understand why my parents relented to my pleas to buy me an air gun, for it was powerful and potentially dangerous. Luckily I never had an accident involving other people, but the sparrow- and starling-populations in our yard shrunk quite a bit. My scarce pocket money for a time went mostly on buying cans with 500 lead pellet bullets. Why I enjoyed aiming at and shooting these creatures is now a mystery but there was then a strong urge for such excitement. I never have allowed my own sons such ‘liberties’.

When in the sixth and last year of our elementary school a decision had to be made about the secondary school to go to. There were about five choices: a technical craftsman school, an agricultural school, an intermediate high school, an academic high school or grammar school and a Latin school, the same as the grammar school but with compulsory Latin and Greek. I wanted to go to the grammar school, where there was a dual emphasis on foreign languages and on math, physics and chemistry. My parents themselves had no secondary education, they were self-taught citizens who got plenty of practice at writing essays and at debating in their churches’ Young Peoples Groups. Such groups were in fact major educational enterprises in our church and made the denomination we belonged to, comprising less than ten percent of the population, influential far beyond this number in Dutch society and politics throughout the twentieth century.

Of course the principal was consulted and I was sent to the intermediate secondary school in Winschoten, where Stiny had also gone two years earlier. This school type was meant largely for future teachers and administrative occupations. English, French, German as well as Dutch were obligatory as were subject packages including math, natural science, geography and history. I wanted to go to the more academically oriented grammar school, but my parents found that a bridge too far. So in August 1949, still twelve years old, I went to cycle the twice seven kilometers to Winschoten each day. The school was pleasant but not very demanding. I had loads of free time and felt resentment that I had not been allowed to choose my own school. By Christmas time my mathematics teacher meester Mulder came to see my parents and urged them to send me to the grammar school the next school year and that is what happened. Of course this meant the loss of another year, but that seemed of no consequence to anybody: doesn’t the Lord give us our lifetime for free? So finally I was in my type of school, with academically trained teachers and a demanding curriculum. I thrived. I disliked homework a lot, there were too many better things to do. So in school I paid careful attention, did nearly all my homework in class or in between hours and had lots of free time for farm work, friends and sports, rowing on the river, shooting with self-made bow and arrow, spear throwing, catapult shooting and the like. My parents never worried about my homework, partly because they had no experience of such a school and secondly because when asked, I challenged them to wait for my next report card.

My parents did regret their earlier decision and to express that they bought me a beautiful sports bike, of the brand Locomotief, a possession that gave me more pleasure than any other new vehicle I ever owned, including my 1965 Ford Mustang, my 1988 BMW-7 or my 2004 Toyota Prius. The sturdy bike was dark red, had effective gears, was very stable and I rode it fast with energetic joy. Suddenly the half hour ride to school became a pleasure I looked forward to.

Of course we remember hard winters and hot summers the best, in fact in our memories those were the only winters and summers there were … a human selection effect. We had lots of water around us, the wide dead straight ditches separating the farms, the meadows between the dikes and the river that were often inundated and the river itself. So when a high pressure region hovered over North-western Europe and sat still for a week or two, our nighttime temperatures sank to minus 10 to 15 Celsius and after two such nights we were skating, first on the meadows, next day on the ditches and finally on the river. Blue skies, a moderate but cold east wind and whole troops of kids were on the ice till sunset. Here all school types, all religions, all politics, all social classes mixed naturally, our immersion in the natural landscape made it so. Wonderful times.

About twice a year Mom’s sister tante Tryn, her husband oom Ekke Bousema, their identical twins Jan and Henk plus their daughter Ina would come to stay a day or two. They were our favourite family. They lived in the city (Groningen), spoke Dutch, were to us quite sophisticated (the twins were three and a half years older than Stiny, by 1949 were already in Teachers College). Ina was a good looking, socially gifted girl, half a year younger than Henk, but in manner, dress and speech way ahead of us locals, therefore regarded with a mixture of curiosity and envy by our friends. We enjoyed showing her off.

Oom Ekke was a tax inspector, had a motorcycle to visit tax-paying businesses, was full of humour to us but apparently feared by his customers. He foolishly let me ride his Zündapp, first as his passenger, then alone. I recall the adrenaline soaring as I felt the power of acceleration and how I had to hang in the curves as those big oak trees flew by. No hanging in there, no way to make the curve. I knew it; oh that felt like scaling an overhung cliff. It would have been better to learn on a road without immovable trees.

Much more relaxed, though still quite exciting, was driving the army jeep of another uncle, Mom’s brother Meindert. He was the steward/estate agent of a Duke in an adjacent province, needed the jeep for visiting his many tenant farmers and the Duke’s forests. Whenever that family of five came to visit us, uncle let me drive his jeep up and down the one km farm lane. The vehicle was open, fun to drive, new experience in addition to that with our model A Ford.

Henk and I at least once a year took the train from Winschoten to Groningen to stay with the Bousemas. Sometimes oom Ekke would take us sailing on a lake. I loved it. Nearly always we asked permission to wander about the city centre for half a day by ourselves and that was usually granted. We would take a bus, get off at the Grote Markt and head for the first movie house we spotted. Movies were considered sinful in our subculture and we never were allowed to see them in Winschoten. In Groningen we were anonymous and we grabbed the opportunity. Cowboys, love stories, wars and treason, we saw it all, usually two movies in one afternoon. We would then walk back, carefully looking at various streets, buildings and parks and concoct a story about how we spent the afternoon. We agreed there had been no sin in our movies to speak of, so no reason to feel guilty! We were however prudent enough not to reveal our true activities. Vaguely we sensed that this was the sin of the afternoon.

About 1949 it was decided to save Blyham churchgoers a second trip to Winschoten, by having the afternoon or evening service (winter or summer respectively) in a kind of simple auditorium in the former café Velema, at the point on the main road Blyham-Wedderveer where the oak trees began. To me it is still not clear whether it was the café character of the space -some people had for a long time been drinking their beer there- or the austerity of the furniture, -row upon row of uncomfortable chairs- that changed people’s behaviour, fact is it was very noisy right up to the entry of minister and consistory members to begin the service. Incredibly, many men smoked right up to that point and when the minister climbed the pulpit for the opening prayer, we from the back could see him only dimly.

Old Mr. Velema had retired not only because his establishment was no longer competitive with the more modern place next door but also because his mental faculties were increasingly prone to failure. So he rented the place to our denomination for one service per Sunday and for catechism and Young People meetings on some weekday evenings. He cleaned the place himself, including the removal of uncounted cigarette butts…

One rainy Sunday afternoon, shortly after the start of service, Mr. Velema came into the auditorium with a pail and a mop on a long stick and proceeded to wipe the leaky ceiling behind the minister. This was not good for our attention to the sermon and soon an elder took Mr. Velema firmly by the arm to remove him with pail and mop from his own auditorium. Interesting church event for twelve year olds.

On New Year’s Eve we always had a service and we boys always had fireworks to tend to. To combine this satisfactorily half a dozen of us brought our bombs and flares and arrows to church, in the dark hid these things behind Velema’s barn and attended the service. As soon as the service ended and the small congregation filed out the door, first explosions marked the special occasion. Henk and I did not have much money for fancy fireworks, so we spent our scarce savings buying carbide -the same ghastly stuff that lit our wartime lamps- from local blacksmiths, preferably in big lumps, which we cut into smaller pieces as needed with a chisel. To effect a big explosion, we had fashioned strong tin cans, for syrup for example, into multiply useable explosive devices. By boring a small hole in the bottom, by distorting the lid so it would jam tightly when stamped on with a heel, we each had a cheap but functioning bang-maker. You put a piece of carbide into the can, poured just a little water on it -for us the quickest and best controlled dose was achieved by peeing on it-, locked the lid, put your foot on the horizontally placed can and lit a match at the bottom hole. Often the thing fizzled because the lid was not tight enough, but frequently the bang was loud. Of course then searching for the lid was a nuisance. One year I had managed to get a small steel milk-can, drilled the bottom hole, distorted the deep-seated strong lid with a hammer and carried it under my coat to church. It needed more carbide, more pee and more daring, with two boys standing on it, but did it give a big bang! That none of us ever had a serious accident doing these crazy things -neglecting burned fingers and sore spots from flying lids- is amazing.

A summer picture of Dad, putting sheaves of oats that have been made with our harvester into the heaps where they were left to dry, then to be loaded on wagons to be taken into the barn. Picture about 1948.

Of course, when the grain was ripe and mown and bundled into sheaves, then put into mounds to dry on the fields, we were ready for harvest proper. We boys were engaged with the adults, loading wagon after wagon. From the age of eleven I was driving the A-Ford from far fields to and into the barn and returning with an empty wagon at high speed for the next load. Just once the load was not properly stacked and the imbalance worsened by a deep rut. I was aghast to see it slowly but surely topple into the ditch next to my lane. The whole rhythm of barn- and fieldwork was gone and I felt miserable that afternoon, till Mom gave me permission for a late swim in the setting sunlight.

In the summer there was always plenty of work after school (our summer holidays lasted a mere three weeks in grade school and one more in high school). Each of us had tasks in the vegetable garden, in looking after chickens, goats, cows and horses, cats and dogs (the cats had uncertain numbers, the dogs were one or two). But we were free to structure our own work as long as it got done properly, so if I got home at 2 pm from school, I would be off to Triton and be splashing in pool 3, diving from the towers, at 3.30, several chores done, sandwich and apple eaten, home work dismissed as trivial. Soon the others came and we would be on the swings so high we could see the girls in the pool or in the pool where we saw the girls in the swings. Incessant howling and laughing, continuous chatter and shrieks, the sounds of healthy kids without a care in the world.

When about eleven, I started organ lessons with a retired postmaster, a kind gentleman. I enjoyed going there and learning my notes, play increasingly difficult tunes and receiving my teacher’s approval. At home we had a wind organ pumped with both feet, an instrument common in many protestant homes. I practiced regularly and became quite adept at playing hymns from the Psalter Hymnal, with sometimes one or more family members singing along.

Our tante Ali, who with her husband oom Albert and daughters Frieda and Stina lived near Blyham, when visiting always asked me to play so she could sing for us all. She was a lovely, delicate woman, a lady I thought too elegant for our town. She was Frisian, did not speak our dialect so we all spoke Dutch when she was with us. That to me underlined her social superiority. I was very fond of her, gladly accompanied her hymns. After the war, oom Albert found work as a supervisor in the Noord-Oost Polder project and was away from Sunday afternoon till Friday night. They lived in the upstairs part of a big farmhouse that I passed each school day on the way to and from Winschoten.

One day in the spring of 1950, nine year old Frieda and six year old Stina found their Mom dead in bed. It was a great shock in the whole family, tante Ali, age thirty-three, apparently had a congenital heart defect that could at that time not be repaired. Stina, who was not only Rika’s cousin but also one of her best friends, died at the age of forty-two of much the same condition. Oom Albert found a dedicated Frisian housekeeper and moved the girls to a new town in the Noord-Oost Polder. He married her at the end of 1951 and she became the tante Tine we came to love in later years. To Albert and Tine a son Henk was born the next year.

Informal working day picture in front of the Wedderveer house about summer 1951. Front left to right: Stiny, Frieda, Henk, Rika, Stina, Co; rear: Dad, Mom and tante Tine.

Picture taken on a sailboat on the Zuidlaarder Meer,

a shallow lake near Groningen, where oom Ekke introduced us to sailing.

Picture taken about 1946.

On the photo periphery starting on the lower left: tante Iet, Mom’s second sister after her; the twin cousins Henk and Jan Bousema; Stiny and cousin Ina Bousema.

Core of picture, left to right: tante Anna and oom Piet Stuit and tante Marie Stuit from the USA (Dakota), tante Tryn – Mom’s sister directly after her and mother of Henk, Jan and Ina.

Oom Piet & tante Marie were brother and sister to oma Beekhuis-Stuit

Church Young People’s group.

Picture from ca 1949.

On the very front-right is Eika, going left slightly up: Ali Feunekes, Eika’s cousin – our neighbour in Eben Haëzer; Ina Bond, Stiny’s life long friend; Lini Lugtenborg, Mindert Kronemeyer.

Just above and to the right of Eika’s head, Berendina and Janny Feunekes, Ali’s younger sisters; left of Janny, Martha, Eika’s older sister; girl to her left and in extreme lower left corner unidentified. Top row from left to right: two brothers Korvemaker, Harry, Dina Bessembinder, Stiny.

Harry’s class at the Winschoten academic high school,

with Harry and his friend Dirk ter Arkel at the very top, Dirk with glasses.

Picture of spring 1953.

Family picture in front of our house in May 1953;

most of us are wearing clothes recently bought for our Canada journey.

Leave a Reply